Services are essential building materials of any data exchange ecosystem, and X-Road is no exception. Therefore, the number of available services is one of the key metrics when measuring the effects and benefits of an X-Road ecosystem.

For clarity, in X-Road, services are technical interfaces between information systems that are not used by end-users directly. Instead, end-users communicate with X-Road services indirectly through other systems and platforms, e.g., using the state portal that fetches information from multiple base registries over X-Road.

Besides the number of services, other important metrics are the number of member organisations and connected information systems, and the amount of data and queries exchanged between the members. However, from the ecosystem perspective, the number of available services may be the most essential metric. According to a study by Kristjan Vassil in 2016, the discrete threshold for ecosystem growth appears at 50 data repositories.

X-Road comes with tools to measure the number of available services in an ecosystem. Since X-Road is based on a decentralized architecture, the X-Road member organizations maintain information about available services locally on their Security Servers. There's no centralized list of available services by default, but the X-Road Operator may collect the data from Security Servers and publish it in a service catalog. For this purpose, the Security Server provides a set of built-in metadata services that can query metadata about the services published by different member organisations. However, interpreting the numbers requires some background knowledge of what the term service means in the context of X-Road. This blog post aims to explain the anatomy of service in X-Road.

Database, dataset, data service, or service?

Over the years, many different terms have been used to describe information systems in service providers' roles in X-Road. The term database was the most used for many years, while the term service has become the most common in recent years. Nevertheless, different terms are still used interchangeably.

Technically, X-Road doesn't distinguish between a database, data set, data service, or service. Also, there's no difference between a data service, a business service, or an aggregated service. Instead, X-Road divides services into SOAP, OpenAPI, and REST. In other words, dividing services into different categories is based on their technical characteristics rather than the type of the service.

Identifying services

In X-Road, all services are identified using a unique service identifier string. The identifier is used to invoke services, and the number of available services in an X-Road ecosystem is counted by calculating the number of service identifiers. The service identifier includes information about the X-Road ecosystem, the organization owning the service, and the information system providing the service. However, the service identifier doesn't contain any information about the service category, but the built-in metadata services can be used to access the category information.

Connecting services

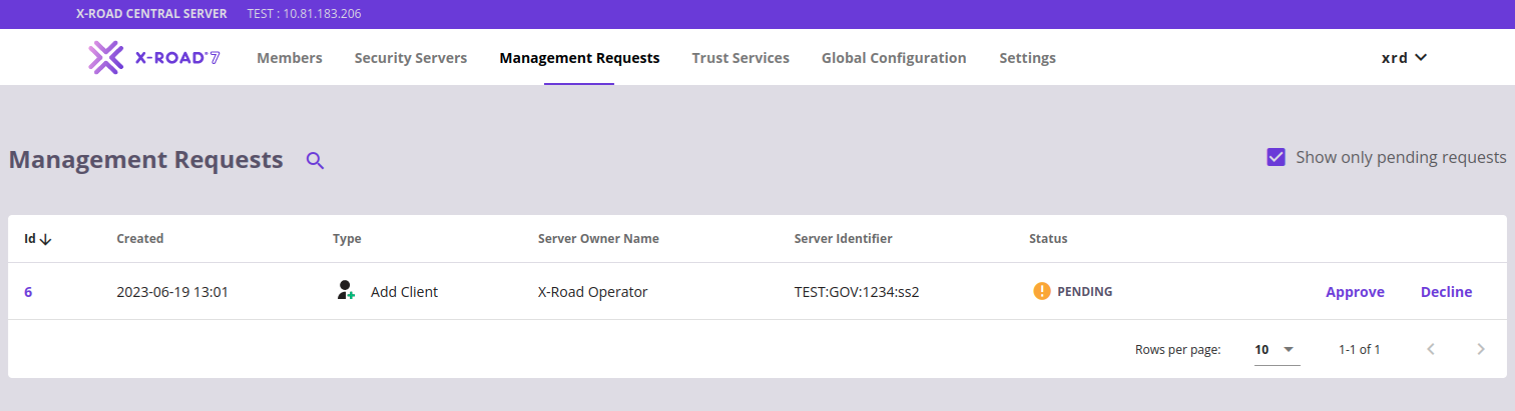

Publishing a service to X-Road requires that the organization owning the service has been registered as a member of an X-Road ecosystem and has access to a Security Server. First, the organization must complete an onboarding process to join an X-Road ecosystem. The organisation’s identity is verified by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA), and the X-Road Operator registers the organization. As a result, the organization is given an X-Road organization identifier.

Security Server is the organisation’s technical access point to the X-Road ecosystem. The organization may deploy its own Security Server, use a shared Security Server, or buy a Security Server as a service from a commercial service provider.

When an X-Road member organization has access to a Security Server, an information system providing a service must be connected to the X-Road ecosystem. In X-Road's terms, it means registering a new subsystem identifier on the Security Server(s) or utilizing an existing subsystem. A subsystem represents an information system or a logical group of information systems. The information system may be in a service consumer role, a service provider role, or both.

The service is then added under the subsystem. If the information system provides multiple services, all the services can be added under the same subsystem. Alternatively, various services published by the same information system can also be added under different subsystems. Access permissions to the services are defined on a service level, so whether the same or different subsystem is used doesn't affect them.

A service can be published on one or more Security Servers simultaneously, and one Security Server can publish multiple services owned by different organisations. For high availability, publishing services on multiple Security Servers is recommended. The Security Server supports high availability in two different ways: internal and external load balancing. The number of Security Servers where a service is published doesn’t affect the service identifier – it’s always the same.

On the other hand, it's also possible to publish the same service under two different service identifiers. For example, a free version of a service is published on a standalone Security Server with no high availability, and a paid version of the same service is published with a different service identifier on a Security Server cluster with external load balancing. That way, it's possible to provide two versions of the same service with different SLAs.

SOAP, OpenAPI, and REST services

X-Road supports three service categories: SOAP, OpenAPI, and REST. Regardless of the category, all the services are identified using a service identifier. However, the way how the services work and are managed varies between different categories.

SOAP

X-Road Message Protocol for SOAP defines how service consumers and service producers communicate with the Security Server. The protocol is based on SOAP profile 1.1. It comes with some X-Road-specific limitations and additional requirements, e.g., support for synchronous request-response operations only, some mandatory SOAP headers are required, and document/literal style SOAP body is required.

A common approach is to have an additional adapter service component between the Security Server and a SOAP client or service. The adapter service implements the X-Road Message Protocol for SOAP and converts all incoming/outgoing messages to/from the X-Road SOAP profile.

SOAP services are connected to the Security Server by providing a URL of a WSDL service description that may contain one or more SOAP service endpoints. The Security Server validates the structure of the WSDL description, but it doesn’t validate the WSDL against the service endpoint implementation.

Typically, a single SOAP endpoint represents a service that implements one action or procedure. Each endpoint has a unique service identifier. Also, endpoints can have multiple versions that have their own identifiers. For example, a WSDL description with four SOAP endpoints counts for four X-Road services since each endpoint gets its own X-Road service identifier.

Access permissions to SOAP services are managed on the service endpoint level. When a single WSDL contains multiple SOAP endpoints, access rights must be defined for each endpoint separately.

OpenAPI

Consuming and producing OpenAPI and REST services via X-Road is possible without an additional adapter service component. X-Road-specific information required by the Security Server (e.g., service client identifier, service provider identifier, message id, etc.) is transferred and processed so that existing REST-style services and service consumers can be connected to X-Road with minimal changes or no changes at all. This is achieved by transferring X-Road-specific information required by the Security Server in HTTP headers and URL parameters outside the message payload. The full details are available in the X-Road Message Protocol for REST document.

OpenAPI services are REST APIs that have an OpenAPI Specification available. The Security Server doesn't set any restrictions to the content type of the API messages, so the content type isn't limited to JSON only.

OpenAPI services are connected to the Security Server by providing a URL of an OpenAPI specification that describes a REST API with one or more API endpoints. The Security Server validates the structure of the OpenAPI specification, but it doesn’t validate the specification against the API implementation.

Typically, REST APIs are resource-centric, and endpoints are used to change the state of resources. However, REST APIs may also be RPC-style and implement actions or procedures. Either way, an OpenAPI service has a unique service identifier that covers all its API endpoints. For example, an OpenAPI service with four API endpoints counts for one X-Road service identifier.

A single OpenAPI service may support multiple API versions, or different API versions may be published as separate OpenAPI services. If the API version is included in the API base path URL (e.g., https://api.example.com/v1), a new OpenAPI service must be created for a new API version. Instead, if the API version isn't included in the base path URL (e.g., https://api.example.com), the same OpenAPI service can access different API versions. Access to the API works so that all the paths under the base path URL are accessible to service clients with sufficient access permissions. Therefore, the base path URL must be defined with caution.

Access permissions to OpenAPI services can be managed on the API and API endpoint levels. Giving access on the API level means providing access to all the API endpoints by default. Also, if the API has endpoints not defined in the OpenAPI specification, they can be accessed too. Instead, giving access on the API endpoint level only provides access to specific endpoints. API endpoint level access permissions are defined using HTTP request method and path combination. Therefore, it is possible to define access rights for a single endpoint or alternatively for a subset of endpoints using wildcards. By default, the Security Server has a list of all the endpoints defined in the OpenAPI specification, but adding new endpoints manually is supported. Security Server’s access rights management only supports allowing access – explicitly denying access is not supported, e.g., allowing access to all endpoints on the API level and denying access to a single endpoint is not supported.

Besides access rights management, the Security Server does not use the endpoint-related information for anything else, e.g., the Security Server does not validate if an endpoint defined in a request by a client information system exists under an API or not. In other words, if a client information system has sufficient access rights to invoke an API endpoint, the Security Server forwards the request to the specified endpoint without any further validations.

REST

REST services are REST APIs that don’t have an OpenAPI specification available. REST services are connected to the Security Server by providing the API's base path URL. A REST service has a unique service identifier that covers all its API endpoints. For example, a REST API with four API endpoints counts for one X-Road service identifier.

REST services can be used to connect any HTTP-based endpoints to the Security Server. The Security Server doesn't set any restrictions to the content type of the API messages, so the content type isn't limited to JSON only. For example, a group of SOAP services could be connected to the Security Server using a REST service. It would be enough to provide the base URL of the SOAP services without a WSDL service description. In that case, the group of SOAP services would count for one X-Road service identifier.

Access permissions to REST services can be managed on the API and API endpoint levels. Giving access on the API level means providing access to all the API endpoints. Instead, giving access on the API endpoint level only allows access to specific endpoints. Since REST services don't have OpenAPI specification that defines the API endpoints, the endpoints must be added manually by the Security Server administrator if they need to be used in access rights management.

Metadata services

The Security Server provides a set of built-in methods that can be used to discover what services are available to them and download the machine-readable service descriptions. These methods are known as metadata services and are accessed using the service metadata protocol for SOAP and the service metadata protocol for REST. The metadata services have separate versions for SOAP and REST services.

Counting members, information systems, and services

The number of registered member organisations can easily be counted based on the member identifiers. Instead, the number of connected information systems can be calculated by the subsystem identifiers. However, the number of subsystem identifiers doesn't directly tell the number of connected information systems since a single information system may have multiple subsystems, and various information systems can share the same subsystem. Therefore, the number of connected information systems is only indicative.

With services, things get more complicated. The number of service identifiers doesn’t directly match the number of connected services. SOAP service endpoints are counted separately, while OpenAPI services are calculated on the API level rather than the API endpoint level. The same applies to REST services as well. However, X-Road supports counting the number of individual API endpoints, too, if they have been defined in an OpenAPI specification or manually.

Nevertheless, the service-related numbers don't say anything about the type of services. For example, they may provide simple access to data, execute a business process, provide service orchestration, etc. Therefore, additional analysis going behind the numbers is needed when comparing the available services of two X-Road ecosystems or evaluating the service coverage of a single ecosystem.

In addition to these metrics, it’s highly recommended the X-Road Operators implement the X-Road Metrics extension to get more detailed insights on the data exchange-related details in the X-Road ecosystem.